Malignant glioma (MG) is a brain tumor that carries a grim outlook for patients, as the disease is characterized by the unavoidable recurrence of the tumor despite the application of different therapeutic interventions. The discovery of better treatments is essential, and the need for this is critical.

On a positive side, Fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide that occurs naturally, can be found in brown seaweed. As reported, Fucoidan demonstrates various biological functions, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, and proapoptotic activities.

The purpose of this blog post is to provide a summary of the study titled, “Epigenetic Modification and Differentiation Induction of Malignant Glioma Cells by Oligo-Fucoidan“ by Chien-Huang Liao et al. The study explores the use of epigenetic modification of oligo fucoidan (OF) derived from brown algae as a promising anti-cancer strategy, as it induces differentiation in MG cells, including grade III U87MG cells and grade IV GBM (Glioma Multiforme) 8401 cells. Natural products are known as a useful source of epigenetic modifiers with a wide safety margin, and their effects were investigated and compared with those of immortalized astrocyte SVGp12 cells.

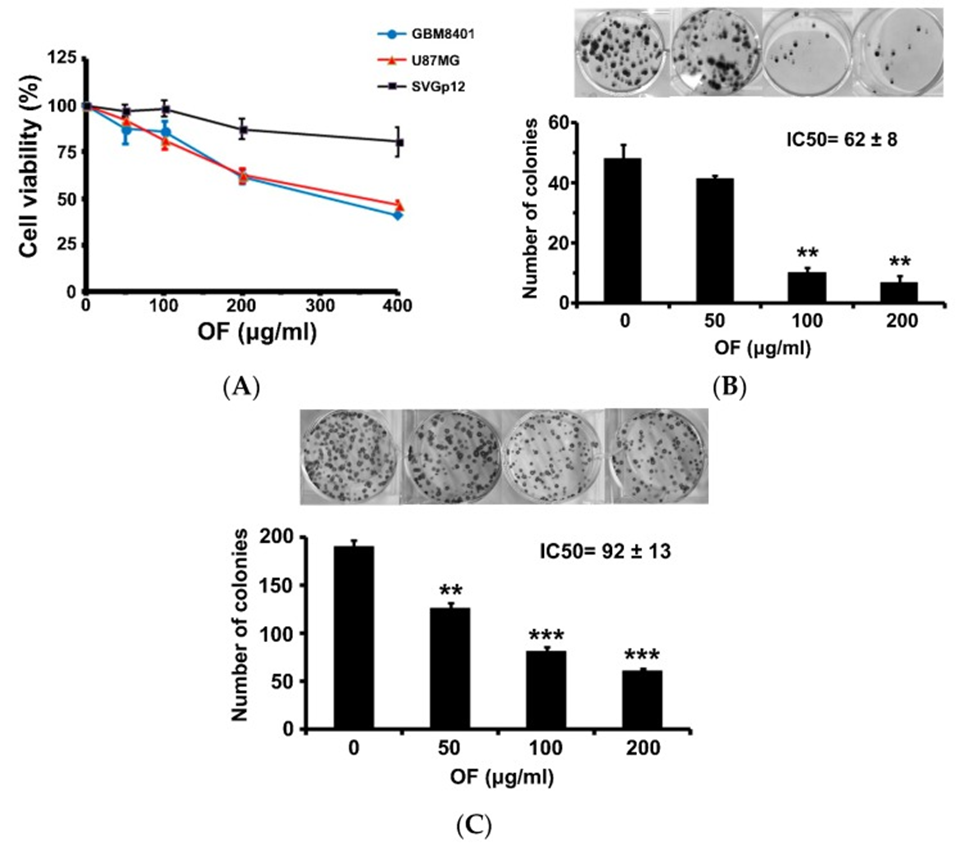

The study began with an investigation into how OF influenced the proliferation of human MG cells (GBM8401 and U87MG), a process evaluated through a sulforhodamine (SRB) assay. After 72 hours of exposure to OF, at a concentration of 400 μg/mL, cell proliferation of GBM8401 and U87MG cells was inhibited to 40% and 46% of control levels, respectively (see Figure 1A). In contrast, OF had only a slight inhibitory effect on the proliferation of immortalized astrocytic SVGp12 cells at the same concentration, suggesting that OF preferentially suppresses cancer cells. When the concentration was 200 μg/mL, colony formation in GBM8401 and U87MG cells was notably reduced, reaching 14% and 32%, respectively (refer to Figure 1B, C). The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of OF on clonogenicity in GBM8401 and U87MG cells after 12 days of treatment were, respectively (see Figure 1B, C). Higher-grade MG cells appeared to be more sensitive to OF.

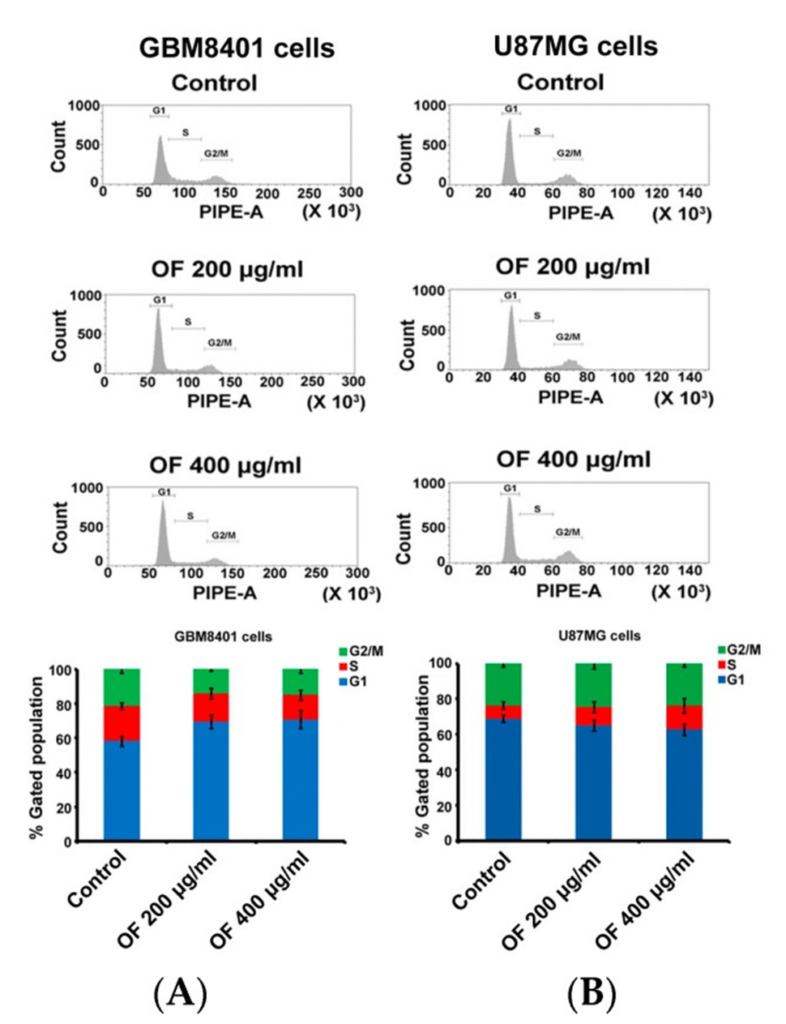

The cell cycle distribution of GBM8401 and U87MG cells is presented in Figure 2A and B, following treatment with OF at concentrations of 200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL for 72 hours. OF arrested the cell cycle of GBM8401 cells by increasing the G1 phase fraction from 58% (control) to 69% and 71%, respectively (Figure 2A). In U87MG cells, OF concentration-dependently increased the S phase fraction from 7% (control) to 10% and 14%, respectively (Figure 2B). The results show that in different types of MG cells, OF can inhibit proliferation by arresting the cell cycle at either the G1 or S phase.

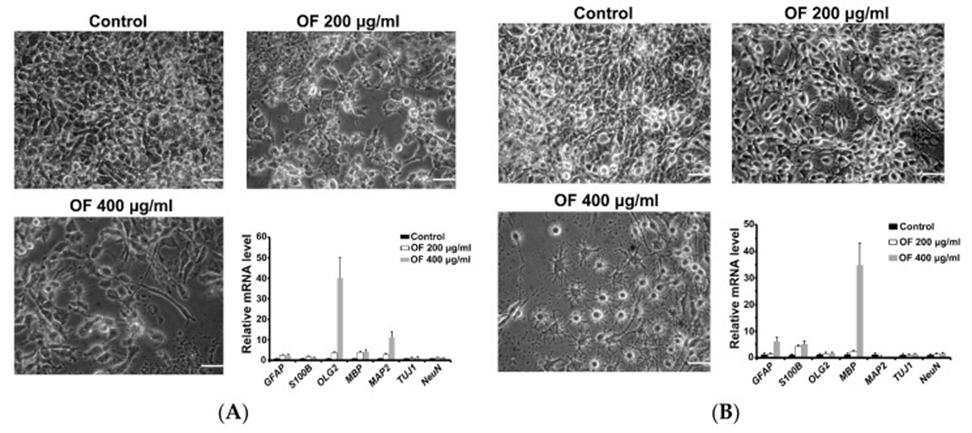

As shown in Figure 2, no apoptosis induction was observed in OF-treated MG cells. However, significant cell shape changes were observed in the morphology of neurons, oligodendrocytes, and glial cells after OF treatment. Based on the evidence, it is proposed that the OF-mediated inhibition of MG cells is likely caused by the process of differentiation induction, rather than through mechanisms that are cytotoxic in nature. To confirm this, quantitative PCR assays were used to measure a panel of early (astrocytic (GFAP), oligodendrocyte (Olig2), neuronal (MAP2 and Tuj1)) and terminal (astrocytic (S-100β), oligodendrocyte (myelin basic protein, MBP), neuronal (NeuN)) differentiation markers in OF-treated MG cells.

The image presented in Figure 3A illustrates how the OF-treated GBM8401 cells displayed cellular shapes that appeared to be similar to those of neurons and oligodendrocytes. Supporting this, early differentiation markers for oligodendrocytes (Olig2) and neurons (MAP2) were significantly elevated in these GBM8401 cells (see Figure 3A). U87MG cells treated with OF (400 μg/mL) showed an increase in oligodendrocyte-like cells and a decrease in glial-like cells (Figure 3B). Correlated with this, a dramatic increase in MBP, a marker of terminal oligodendrocyte differentiation, and a significant increase in astrocyte markers (GFAP and S100B) were detected in these U87MG cells as shown in Figure 3B. According to the data obtained, it appears that OF might have the capacity to trigger redifferentiation in MG cells, specifically those that have been transformed into a cancerous state by the dedifferentiation occurrences detailed in Section 1.

After that, the group examined the molecular pathways that govern how MG cells differentiate in response to OF treatment. Epigenetic regulation, including DNA demethylation, is known to play an important role in MG cell differentiation. Therefore, we investigated whether DNMTs in MG cells are inhibited during OF-induced differentiation. As expected, OF suppressed DNMT protein levels in both GBM8401 and U87MG cells. Epigenetic regulation, including DNA demethylation, may play an important role in OF-induced differentiation.

The significant inhibition of DNMT3B protein levels by OF in U87MG cells may have reduced p21 gene methylation and restored its expression. OF induced p21 mRNA and protein levels in a concentration-dependent manner in U87MG cells. Methylation analysis of the p21 gene via methyl-specific PCR revealed that OF administration increased the proportion of the unmethylated (U) p21 promoter and decreased the proportion of the methylated (M) p21 promoter. The U/M ratio in control U84MG cells was 0.89, but increased with OF at concentrations of 200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL, respectively. The known demethylating agent decitabine (5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine), used as a positive control, increased the U/M ratio of the p21 gene at a concentration of 5 μM. Given that p21 acts as a tumor suppressor and a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor, the epigenetic activation of its expression might be crucial for OF to hinder the growth of MG cells. It is possible that the repressed differentiation marker genes may be epigenetically induced by OF through a similar mechanism of action in demethylation.

Due to OF’s substantial demethylation impact, combining it with decitabine might provide a different approach to epigenetic MG therapy through demethylation. Even at a maximum concentration of 10 μM, decitabine only slightly inhibited the proliferation of GBM8401 and U87MG cells, to 64% and 70% of control levels, respectively. When combined with OF (400 μg/mL), decitabine reduced the proliferation of GBM8401 and U87MG cells to less than 40% of control levels. In contrast, immortalized astrocyte SVGp12 cells were much less sensitive to the combined effects of decitabine and OF, suggesting that this combination is selective for MG cells. The combination effect was further examined by the combination index (CI). Since the CI values were below 1 for both GBM8401 and U87MG cells, the combination’s effect was synergistic concerning MG cell proliferation. The CI value for decitabine and OF combined in SVGp12 cells was higher than 1; thus, they appear to work antagonistically to impede cell growth.

The inhibitory effect on cell growth was matched by OF at 100 μg/mL, which also markedly improved the ability of 2.5 μM decitabine to trigger U87MG cell differentiation. The expression of oligodendrocyte-like morphology induced by OF or decitabine in U87MG cells was significantly enhanced in the combination treatment group. Supporting this, treatment with OF or decitabine alone induced mRNA expression of the terminal differentiation marker MBP 7-fold and 180-fold, respectively, compared to the control group. In U87MG cells treated with the combination, MBP expression was significantly enhanced 357-fold compared to the control group. Therefore, the combination of OF and decitabine showed a clear synergistic effect on MG cells, as evidenced by the observed changes in morphology, which resulted in not only the inhibition of cell proliferation but also the induction of differentiation.

According to the results, OF induces the expression of differentiation markers in MG cells, and this process is linked to mediated DNMT inhibition. The combined effects of decitabine on MG cells show that OF could present a complementary approach for epigenetic differentiation therapy of MG.

Source: Mar Drugs. 2019 Sep 8;17(9):525. doi: 10.3390/md17090525