Oral cancer, which accounts for the majority of head and neck malignancies, also presents a significant disease burden to those affected. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, while helpful treatments for oral cancer alongside surgery, come with the potential for serious side effects. Alternatively, fucoidan has been found to have various beneficial effects, such as reducing inflammation, preventing blood clotting, fighting against bacteria, and combating cancer. Much remains unknown, particularly regarding its selective antiproliferative activity and oxidative stress-related responses.

This blog post will discuss the study by Jun-Ping Shiauet al, titled “Brown Algae-Derived Fucoidan Exerts Oxidative Stress-Dependent Antiproliferation on Oral Cancer Cells.”

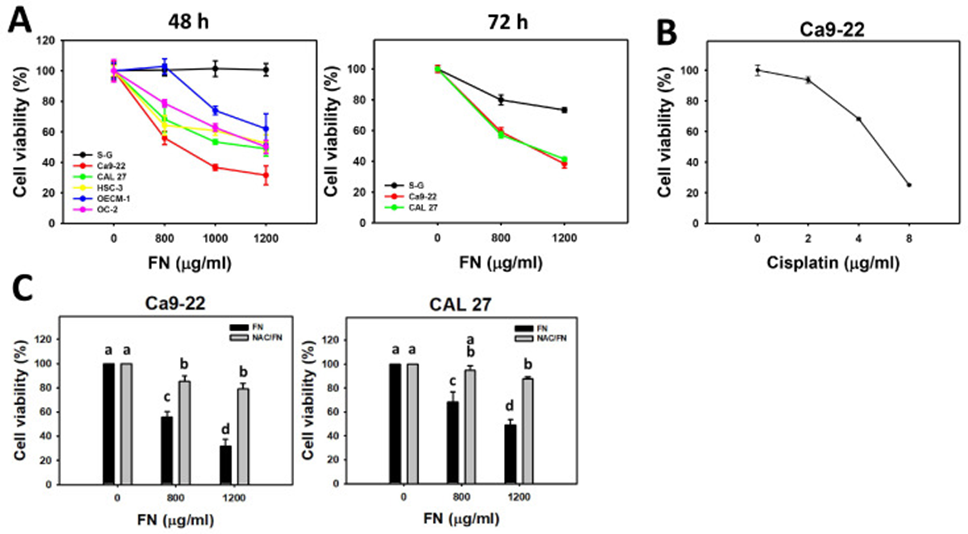

The researchers started by studying the antiproliferative impact of fucoidan on oral cancer cells versus non-cancerous oral cells (S-G), and they investigated the underlying process. Fucoidan dose-dependently decreased cell viability (%) at 48 hours in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22, CAL 27, OC-2, HSC-3, and OECM-1), whereas it maintained cell viability in non-malignant oral cells (S-G) (Figure 1A). Similarly, fucoidan dose-dependently decreased cell viability (%) at 72 hours in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL 27), whereas S-G cells showed higher viability than oral cancer cells.

As a result, fucoidan treatment specifically reduced proliferation in cancerous oral cells, while non-cancerous oral cells were unaffected. The researchers chose oral cancer cells, Ca9-22 and CAL 27, for the upcoming experiment, to examine the intricate mechanism, given that these cells exhibit a high degree of sensitivity to fucoidan. Cisplatin served as a positive control for oral cancer cells (Ca9-22) after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 1B). In addition, the antioxidant NAC counteracted the antiproliferative effect of fucoidan on oral cancer cells (see Figure 1C), implying that oxidative stress played a role.

Fucoidan treatment was followed by the creation of cell cycle histograms for oral cancer cells and non-cancerous oral cells (S-G). In dose and time experiments, fucoidan-incubated oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL 27) showed an increase in the number of sub-G1 and G1 phase cells and a decrease in the number of G2/M phase cells compared to the control group. In contrast, fucoidan-incubated S-G cells did not show an accumulation of sub-G1 phase cells. When conducting dose experiments, S-G cells that were incubated with fucoidan experienced a reduction in the number of G1 phase cells at concentrations of 800 and 1200 μg/mL, along with an increase in the number of G2/M phase cells at 800 μg/mL, although no alteration in the G2/M phase was detected at 1200 μg/mL.

Fucoidan-incubated S-G cells in the time experiments did not have any changes in their cell cycle phase compared to the control group, but there was a drop in the G1 phase after 48 hours. The impact of NAC on reviving fucoidan-treated oral cancer cells’ viability brought up questions regarding oxidative stress’s role in cell cycle progression. The antioxidant NAC reversed the fucoidan-induced accumulation of sub-G1 phase in oral cancer cells. In addition, NAC decreased the G1 phase expansion caused by fucoidan and amplified the G2/M phase in Ca9-22 oral cancer cells. In contrast, NAC increased the fucoidan-induced G1 phase increase and decreased G2/M phase in oral cancer cells (CAL 27) and S-G cells. These results imply that oxidative stress is necessary for fucoidan to regulate the cell cycle’s progression.

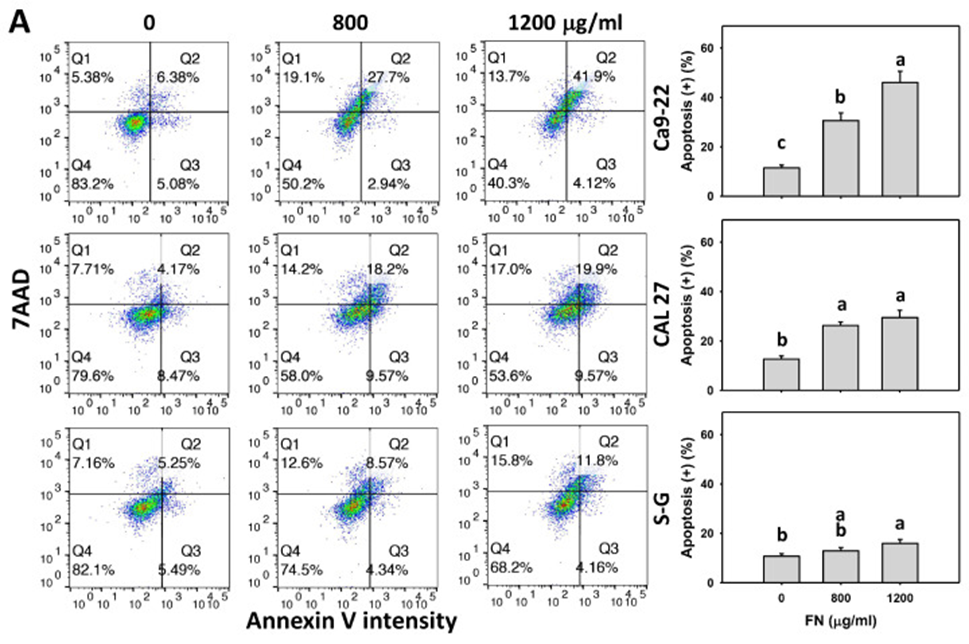

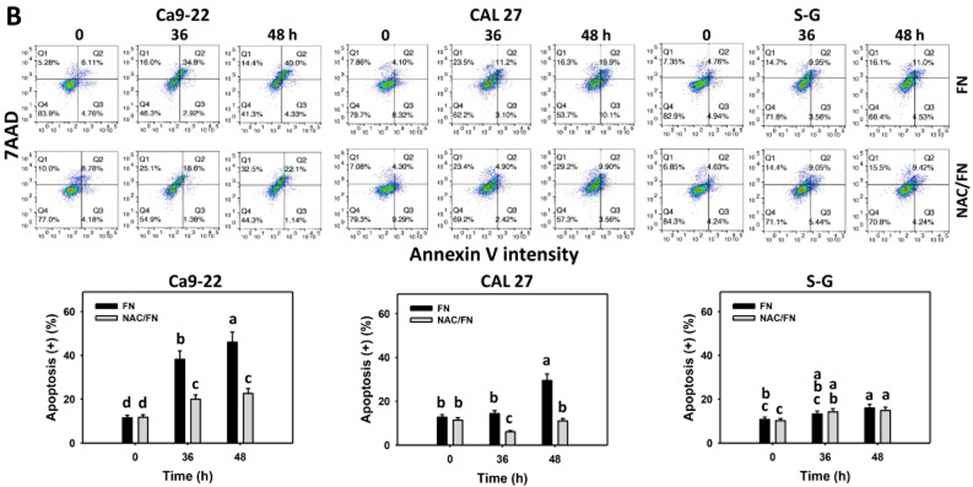

Annexin V identifies phosphatidylserine’s movement to the outer membrane, which is directly related to the extent of cell death. According to the Annexin V/7ADD assay results from experiments involving different doses and durations, fucoidan elevated the Annexin V(+) cell count in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL27) compared to non-cancerous oral cells (S-G) (see Figure 2A, B). This suggests that fucoidan induces preferential apoptosis in oral cancer cells. Also, we were concerned about how oxidative stress affected the process of apoptosis regulation. The antioxidant NAC reversed the fucoidan-induced increase in Annexin V in oral cancer cells (see Figure 2B). The results indicate that oxidative stress is necessary for fucoidan to trigger apoptosis.

The activation of Cas3, 8, and 9 was observed through the release of fluorescence when peptides were cut, correlating with the activation of these apoptotic signals measured via flow cytometry. Flow cytometry density plots are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. Based on dose and time experiments, fucoidan increased the Cas3, 8, and 9(+) population in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL 27) compared with non-malignant oral cells (S-G). This shows that fucoidan preferentially activates Cas3, 8, and 9 in oral cancer cells. The activation of Cas3, 8, and 9, in relation to oxidative stress, presented a concern. The antioxidant NAC reversed the fucoidan-induced increase in Cas3, 8, and 9 in oral cancer cells. This suggests that oxidative stress is essential for fucoidan-induced activation of Cas3, 8, and 9.

Oxidative stress (ROS and MitoSOX) and the intracellular antioxidant GSH were detected. According to experiments involving dosage and duration, fucoidan elevated the levels of ROS and MitoSOX(+) in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL 27) to a greater extent than in non-cancerous oral cells (S-G). Additionally, fucoidan caused a greater reduction in the GSH(+) population within oral cancer cells compared to S-G cells. GSH levels in S-G cells remained unchanged after fucoidan treatment. The findings suggest that fucoidan specifically triggers oxidative stress and reduces GSH levels in oral cancer cells. Further, the effects of oxidative stress and GSH alterations were of concern. The antioxidant NAC reversed the fucoidan-induced increase in ROS and MitoSOX. NAC partially restored GSH depletion in oral cancer cells after 48 hours of treatment. It is evident that oxidative stress is crucial for fucoidan to produce ROS and MitoSOX, and this process is correlated with a decrease in GSH levels.

The development of oxidative stress is caused by the suppression of antioxidant signaling. After the addition of fucoidan (0, 800, 1200 μg/mL), mRNA expression of antioxidant signaling genes, such as NRF2, TXN, and HMOX1, was detected. Fucoidan dramatically downregulated these antioxidant genes in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL 27), but not in non-malignant oral cells (S-G). In S-G cells, these antioxidant genes remained at their base levels when exposed to 800 μg/mL, but were mildly elevated at 1200 μg/mL. According to the results, fucoidan tends to reduce antioxidant signaling in oral cancer cells.

The study revealed that DNA was damaged, and this was confirmed by finding γH2AX and 8-OHdG. Fucoidan increased the γH2AX(+) and 8-OHdG(+) populations in oral cancer cells (Ca9-22 and CAL27) but not in nonmalignant oral cells (S-G). The data imply that fucoidan selectively damages DNA in oral cancer cells. Another concern was how oxidative stress affected DNA damage. The antioxidant NAC reversed the fucoidan-induced increase in γH2AX and 8-OHdG in oral cancer cells. Hence, according to these findings, oxidative stress is indispensable for the γH2AX and 8-OHdG DNA damage that fucoidan induces.

In conclusion, the study revealed that fucoidan affected oral cancer cells by changing cell cycle progression, prompting apoptosis, activating intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways, boosting oxidative stress, suppressing antioxidant signaling, and repairing DNA damage. At the same time, healthy cells showed a reduced frequency of these occurrences. Fucoidan’s ability to selectively prevent the growth of cancer cells is due to the differences it exploits between cancerous and non-cancerous oral cells.

Source: Antioxidants (Basel). 2022 Apr 26;11(5):841. doi: 10.3390/antiox11050841

Great breakdown! For content creators, the AI Tiktok Assistant from tyy.AI Tools could really streamline video production and strategy planning.

Thank you for your a good suggestion, but I like doing now without AI.

Thank you again