Cardiac remodeling plays a key role in the advancement of heart disease and commonly causes heart failure. Galectin-3 (Gal-3), a β-galactoside-binding lectin, has emerged as a key mediator of cardiac remodeling. Elevated Gal-3 levels are associated with poor cardiac prognosis, including fibrosis and inflammation, making it a potential therapeutic target. Previous studies have demonstrated that Gal-3 inhibition can reduce myocardial injury following ischemia-reperfusion injury and improve cardiac prognosis. Fucoidan, a sulfated polysaccharide derived from brown algae, has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anti-fibrotic properties, suggesting its potential as a cardioprotective agent.

This blog post will discuss the research conducted by Wen-Rui Hao and colleagues, titled “Fucoidan Attenuates Cardiac Remodeling by Inhibiting Galectin-3 Secretion, Fibrosis, and Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Pressure Overload.”

The purpose of the research was to assess if fucoidan could suppress Gal-3 and reduce cardiac remodeling. First, Normotensive mice were subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery to induce pressure overload, reproducing the pathological features of cardiac hypertrophy. Mice were administered 1.5 or 7.5 mg/kg/day of fucoidan.

The effects of fucoidan administration on heart and left ventricular weights in TAC-induced hypertrophy were found to be noteworthy in Male C57BL/6J mice models. TAC surgery significantly increased heart and left ventricular weights. However, in the fucoidan-treated TAC group, these weights were reduced compared to the untreated TAC group, indicating an attenuation of hypertrophy. The results of this study indicate that fucoidan may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy, probably because it can regulate oxidative stress and inflammation, therefore reversing hypertrophic remodeling.

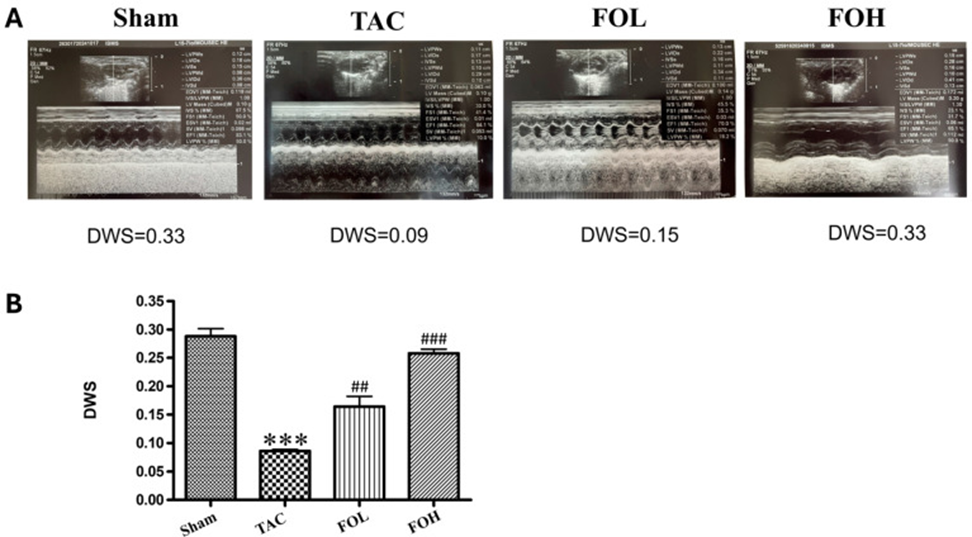

Echocardiographic evaluation revealed differences in structural parameters between the experimental groups (Figure 1A), with improved cardiac function observed in the fucoidan-treated group. Fucoidan treatment led to considerable improvements in key parameters like diastolic wall strain (DWS), while the TAC-treated group demonstrated a partial recovery in ejection fraction when contrasted with the group that didn’t receive treatment (Figure 1B). These findings suggest that the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of fucoidan play a role in cardio protection during hypertrophic stress.

Analysis of left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) and end-systolic volume (LVESV) revealed significant increases in the TAC group compared with the sham group, reflecting ventricular dilation and impaired cardiac function. Fucoidan treatment (both the FOL and FOH groups) significantly reduced these volumes, suggesting attenuation of maladaptive ventricular remodeling. Ejection fraction (EF), an important indicator of cardiac function, was reduced considerably in the TAC group compared with the sham group, indicating systolic dysfunction. Fucoidan treatment partially restored EF, with greater improvement in the FOH group than in the FOL group. This improvement in EF supports the hypothesis that fucoidan treatment improves cardiac function in addition to reducing structural remodeling. Furthermore, fucoidan administration tended to normalize left ventricular internal diameters at end-systole (LVIDs) and end-diastole (LVIDd), as well as left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPWd). These results, taken as a whole, hint that fucoidan might be helpful in treating cardiac hypertrophy by improving the structural and functional issues connected to it.

There was minimal difference in the interventricular septum thickness measurements at end-diastole (IVSd) and end-systole (IVSs) across the groups. This indicates that fucoidan’s influence on heart remodeling and function is targeted, primarily affecting how the ventricles function during relaxation and contraction.

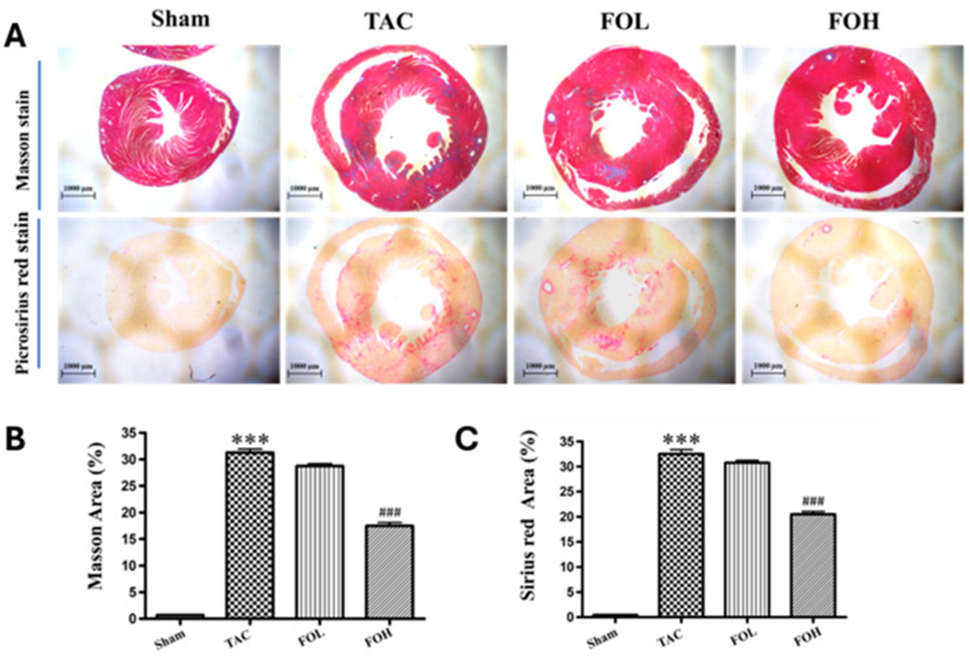

The TAC group exhibited extensive myocardial inflammation, necrosis, structural disorganization, and a notable increase in collagen, suggesting fibrosis, as shown by histological staining with Masson’s trichrome and Sirius red (Figure 2). Fucoidan administration attenuated these pathological changes, including collagen accumulation in the left ventricle, as indicated by a reduced fibrosis area, suggesting a protective role against fibrosis.

The reduced collagen formation and myocardial disarray demonstrate how fucoidan can prevent fibrosis and keep the structure of an enlarged heart intact. This effect may be due to fucoidan’s modulation of both inflammatory and antioxidant pathways, as previously noted in cardiovascular studies.

The ELISA method revealed that the concentration of serum Gal-3 was considerably higher in TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy, and this was connected to the progression of fibrosis. Fucoidan administration reduced Gal-3 accumulation in the intervention group. This suggests that fucoidan may counteract fibrotic signals through downregulation of Gal-3 and potentially alleviate adverse remodeling under pressure overload conditions.

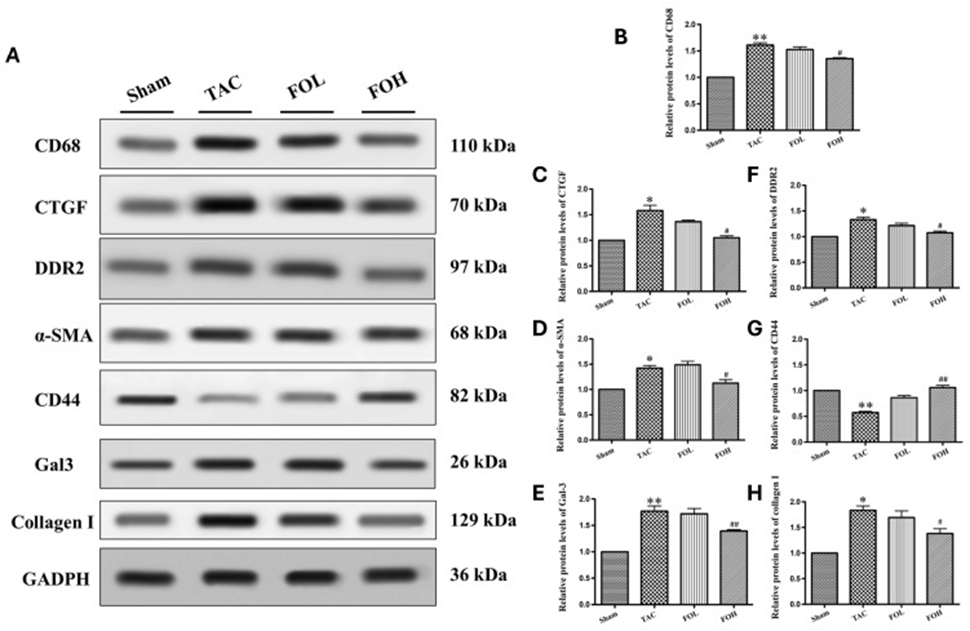

The levels of Gal-3, CD68, CTGF, DDR2, α-SMA, and type I collagen, which are markers for fibrosis and inflammation, increased significantly in western blot analysis following TAC (Figure 3). However, fucoidan administration reduced the expression of these proteins, indicating attenuation of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic responses. Notably, fucoidan restored CD44 expression in the TAC model. CD44 is involved in cell adhesion and migration, which are essential for tissue repair, suggesting that fucoidan may have a specific mechanism for suppressing fibrosis through receptor modulation.

Fucoidan’s influence on inflammation and fibrosis, which manifests in multiple ways, is attributed to its capacity to reduce the activity of various pathways linked to cellular stress and structural changes. By reducing markers such as Gal-3, CD68, CTGF, DDR2, α-SMA, and type I collagen (Figure 3B-F, H), and by modulating CD44 (Figure 3G), fucoidan appears to inhibit hypertrophy progression through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms. These results are consistent with previous studies highlighting fucoidan’s ability to attenuate inflammatory and fibrotic responses, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent for managing hypertrophic heart disease through comprehensive pathway modulation.

According to the data obtained, fucoidan appears to be a potential therapeutic agent that can prevent or delay cardiac remodeling and related complications like fibrosis and inflammation in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, which makes it a promising option.

Source: Biomedicines. 2024 Dec 14;12(12):2847. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12122847